Clinical Integration Isn’t Optional, It’s the Future of Healthcare Supply Chains

Healthcare supply chain decisions that have a direct impact on patient care are too often made outside the view of physicians, nurses and clinical staff. When the right voices aren’t at the table, hospitals run the risk of swapping out critical devices without clinician input, introducing unnecessary variation and increasing costs for both patients and health systemss

By bringing physicians and clinical leaders into the decision-making process, hospitals and health systems can ensure that cost-cutting initiatives don’t come at the expense of patient care. This shift toward a clinically integrated supply chain doesn’t just reduce waste—it improves outcomes, fosters trust, and strengthens the alignment between supply chain teams and frontline caregivers.

Below, we share how our two organizations—Baptist Health and Providence—have embraced this model. Throughout, we offer our unique perspectives: one as a former surgeon turned supply chain leader (Dr. Patrick Osam, Baptist Health) and the other as a nurse-turned-clinical resource integration expert (Guy Love, Providence). Through physician engagement, data-driven decision-making and a structured approach to value analysis, we’ve seen firsthand how supply chain can evolve from an administrative function into a strategic clinical partner.

The Case for Clinical Integration: The Dyad Model of Leadership

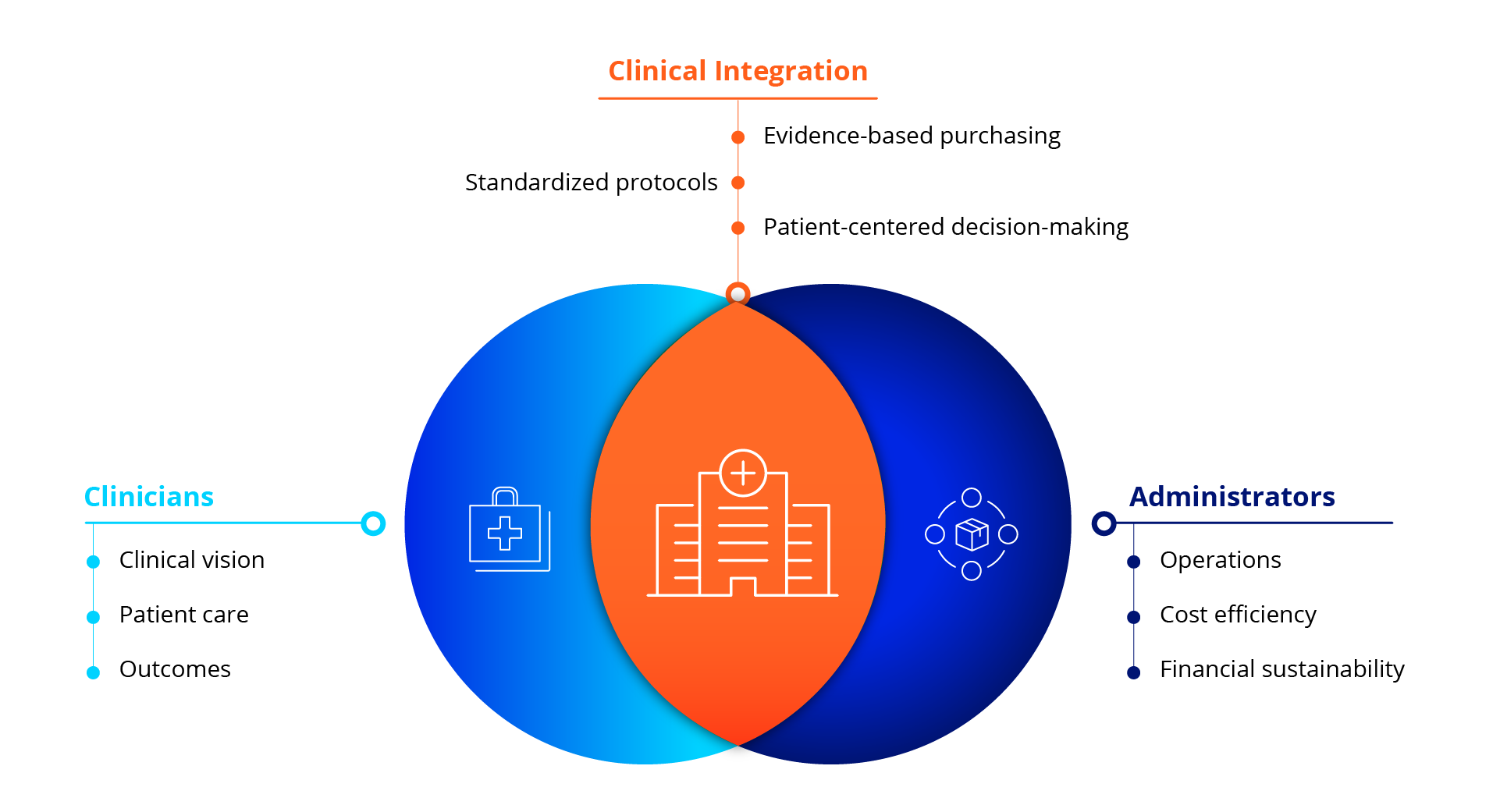

A clinically integrated supply chain isn’t just about cutting costs or improving efficiency—it’s about balancing clinical priorities with operational realities. The dyad model of leadership is at the core this approach, ensuring both clinical and administrative perspectives are represented in decision-making.

Physicians focus on clinical vision and patient care. Administrators focus on operations and financial sustainability. Neither can succeed without the other.

Historically, these two groups have operated in silos, leading to decisions that either prioritize financial efficiency at the expense of patient care—or clinical autonomy without consideration of cost. But true system-wide integration happens when these groups work together.

Dr. Osam’s Perspective: Putting the Patient First

Physicians believe that if they didn’t bring patients, hospitals wouldn’t exist. Administrators believe that without the hospital infrastructure, physicians wouldn’t have a practice. Both are missing the point—the patient is at the center of everything we do.

The dyad model provides a structured framework to bridge this historical divide. By using this dyad approach, hospitals can bridge the gap between financial and clinical stakeholders, ensuring that procurement decisions don’t just optimize cost but also improve patient care and outcomes.

One example of this model in action is the Clinical Quality Value Analysis (CQVA) committee, where physicians and supply chain leaders collaborate to evaluate products based on patient outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and operational impact.

Bridging the Gap: Why Clinicians Are Stepping Into Supply Chain

For years, supply chain decisions were made with little to no clinical input. But that’s changing as more hospitals recognize the need for physician and nurse engagement in value analysis. Our own paths to this work came from personal experiences—moments when we realized that procurement decisions, often made without clinician involvement, were affecting both patient care and hospital finances.

Dr. Osam’s Perspective: A Surgeon’s Wake-Up Call

The first moment that pushed me into this work was the frustration of arriving at the OR to find that the devices I had used the day before were suddenly unavailable. When I asked why, the response was, “Well, they decided to change it.” But who was they? No one could answer.

The second moment came when I noticed that items were being added to my surgical field that I had never requested. I later discovered these additions resulted in extra charges for my patients—some of whom had high copays. That was both ethically and morally wrong. I realized I needed to understand how products made their way into our system and how these decisions were being made.

Guy’s Perspective: The Cost of Unchecked Variation

As an OR nurse, I saw firsthand how product variation impacted both costs and outcomes. One of the biggest red flags was the price difference between endomechanical staplers—two brands that performed the same function, yet one cost significantly more than the other.

I started asking the question: Why are we allowing such drastic pricing differences for products that deliver the same clinical results? This eventually led to the formation of a value analysis committee that began tackling standardization across five hospitals.

These moments aren’t unique to us. Across healthcare, more clinicians are stepping into supply chain roles because they see how product choices affect patient care. Hospitals that embed physicians and nurses into value analysis decision-making ensure that purchases are driven by clinical evidence rather than supplier influence or cost alone.

The Impact of Clinical Integration on Patient Care and Costs

A clinically integrated supply chain isn’t just about saving money—it’s about ensuring that procurement decisions lead to better patient outcomes. When supply chain teams and clinicians work in silos, product selection can be driven by cost alone, without considering how those choices impact quality of care. But when clinicians are involved in decision-making, hospitals can balance cost-efficiency with evidence-based product selection, leading to safer, more effective treatments.

One of the most important benefits of clinical integration is standardization. Hospitals often face significant variation in the products used for the same procedures, with no clinical justification for the differences. This drives up costs, creates inefficiencies and sometimes even introduces risks for patients. By aligning purchasing decisions with clinical evidence, hospitals can reduce unnecessary variation while improving patient care.

Dr. Osam’s Perspective: Clinical Integration in Action

One of the first projects I worked on after stepping into a supply chain leadership role involved pressure ulcer prevention. Nurses on the floors were seeing an increase in hospital-acquired pressure ulcers and wanted to trial a new product.

Instead of pushing for an immediate solution, we conducted a study. The nurses collected data, and the results showed that the new product significantly reduced the incidence of pressure ulcers. That objective evidence justified making the switch—not just from a financial standpoint, but because it directly improved patient outcomes.

Guy’s Perspective: Addressing Product Variation in Surgery

One of the biggest cost variations I noticed as an OR nurse was in surgical staplers. We were purchasing multiple brands at wildly different price points, despite clinical evidence showing no difference in outcomes.

When I raised this with leadership, it led to the formation of a local value analysis committee across five hospitals. By removing product variation and standardizing our selection to the most cost-effective option that still met clinical needs, we not only saved millions but also improved operational efficiency and reduced patient risk.

When hospitals embrace clinical integration, cost savings and patient benefits go hand in hand. Standardization reduces unnecessary spending, but more importantly, it ensures that decisions are made based on clinical data rather than financial pressure alone.

Overcoming Physician Resistance and Building Trust

One of the biggest challenges in clinical integration is engaging physicians in supply chain conversations. Historically, many doctors have been skeptical of procurement decisions, often viewing them as administrative mandates rather than clinically driven improvements. The key to overcoming this resistance is to foster trust—both in the data being presented and in the individuals leading the discussions. Physicians are trained to rely on evidence, so when supply chain teams engage them with accurate, clinically relevant data, they’re more likely to listen. And when these discussions are led by their peers—physicians and nurses who understand the clinical impact of supply chain decisions—resistance turns into collaboration.

Dr. Osam’s Perspective: The “Osam Syndrome” and Physician Engagement

I often joke that when administrators walk into a room to talk about supply chain, something happens: Physicians go deaf, dumb, and blind. I haven’t officially named it yet, but maybe I’ll call it the Osam Syndrome—the instinctive resistance doctors feel when a conversation seems like it’s coming from the administrative side rather than a peer.

It’s not that physicians don’t care; it’s that they’ve seen too many supply chain decisions made without their input. So, when a hospital leader starts talking about product standardization or contract compliance, their guard immediately goes up.

That’s why I approach these conversations differently. I don’t start with cost. I start with clinical impact—how a product affects patient outcomes, safety, and efficiency. And sometimes, something as simple as wearing my old scrubs or white coat instead of a suit can make a difference. When I approach a surgeon as a peer, rather than an administrator, I get a completely different response. That’s why having clinicians lead these discussions i

Guy’s Perspective: The Role of Data in Changing Minds

If physicians are presented with information that’s even slightly off, they tend to believe the entire process is flawed. That’s why we take a slow, methodical approach to rolling out new analytics tools.

By prioritizing trust—both in relationships and in data—hospitals can move past resistance and create real collaboration between clinicians and supply chain teams.

The Power of Physician Champions

One of the most effective ways to engage physicians in supply chain discussions is by leveraging physician champions. These trusted peers can present supply chain data in a way that resonates with clinicians.

When physicians hear recommendations from their own colleagues, rather than from administrators, they are far more likely to buy in. Baptist Health’s cardiac rhythm management (CRM) initiative is a prime example. Instead of supply chain dictating a change, Baptist Health engaged a respected physician champion to lead the discussion.

Dr. Osam’s Perspective: A Peer-Led Approach to Change

We started by presenting utilization data to a trusted cardiologist and the VP of the service line. Instead of us saying, ‘You need to meet these contract commitments,’ our physician champion took the data to his peers and said, ‘Here’s what the numbers show—how can we improve?’ That completely changed the conversation. Instead of resistance, we saw engagement and collaboration.

By having a peer lead the conversation, physicians were more receptive, and the shift toward contract compliance and standardization happened organically. This same approach has since been expanded across multiple service lines, including general surgery, gastroenterology, interventional radiology, plastic and reconstructive surgery, and orthopedics and spine surgery.

Understanding Physician Mindsets: The Bell Curve and Influencing the Middle Majority

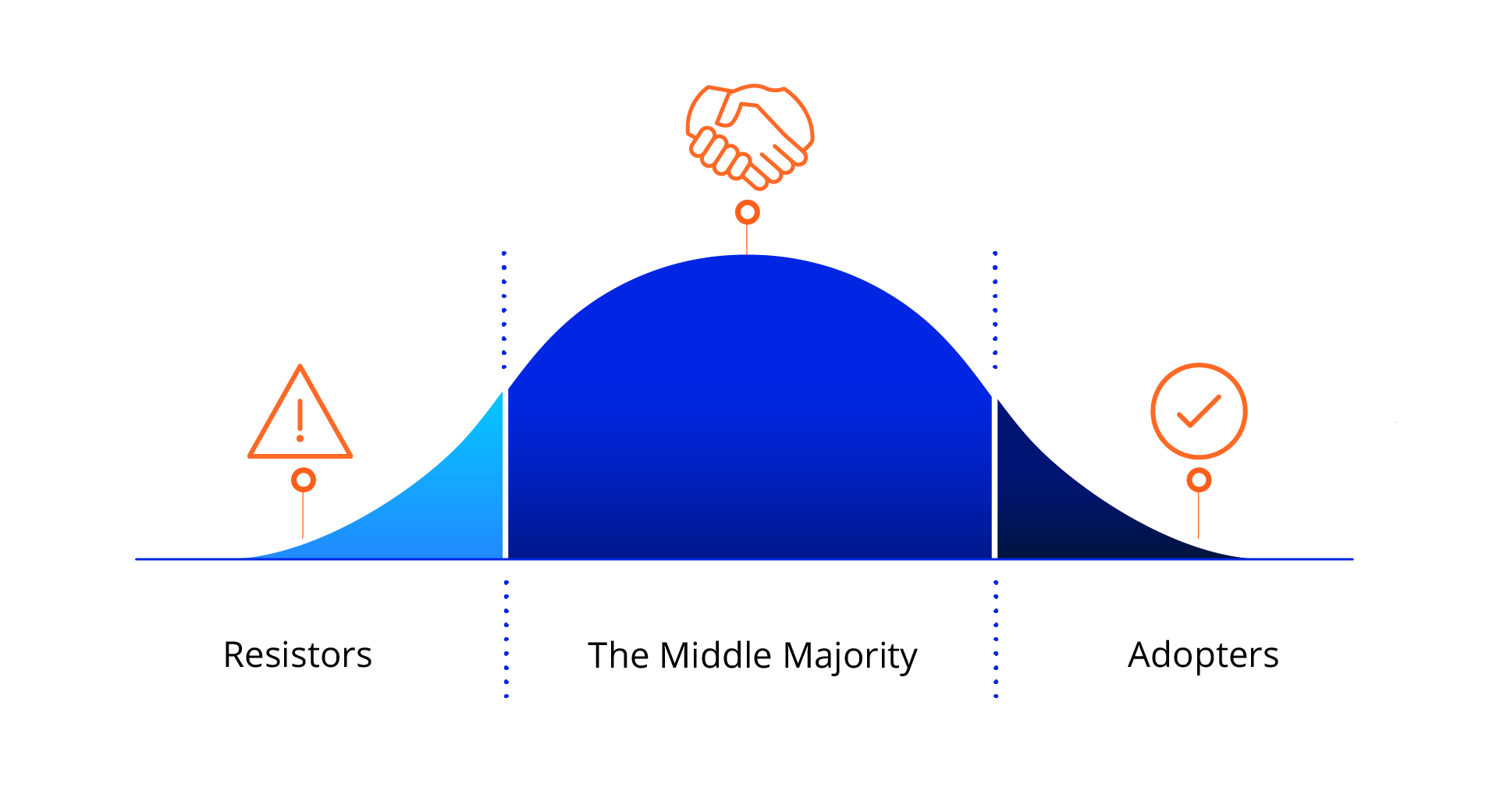

Not all physicians respond to supply chain discussions the same way. In fact, engagement typically follows a bell curve distribution:

- Resistors (Left End): Oppose change, distrust supply chain data, and prefer to rely on personal experience.

- The Middle Majority: The key group to influence. This segment is open to evidence but needs trust, data validation and peer engagement before fully committing to changes.

- Adopters (Right End): Proactively seek innovation, trust clinical evidence and are open to collaboration on product decisions.

Dr. Osam’s Perspective: Meeting Physicians Where They Are

Before engaging a physician on a supply chain discussion, I try to assess where they fall on this spectrum. If they’re an early adopter, they’re already looking for ways to improve. But if they’re resistant, a direct conversation about costs won’t work. That’s when we focus on patient impact, clinical evidence, and—most importantly—having their peers lead the discussion.

Recognizing these differences allows supply chain teams to tailor their approach, using physician champions, validated data and strategic framing to influence the middle majority and shift the conversation toward collaboration rather than resistance.

A good example of this in action is when Providence was faced with an expensive spinal implant supplier. Rather than dictating change, the clinical resource integration team sat down with the neurosurgeons in the middle majority and, deferring to their expertise, asked: “Can you help us understand this cost difference?”

Guy Love’s Perspective: Give Physicians an Opportunity to Drive the Conversation

I simply said to them: ‘I know you all are the experts, so help me understand what I’m seeing here.’ I let them drive the conversation. Once they saw the data up close, they were outraged by the price variance—they couldn’t justify the additional cost. Surgeons led the decision to stop using that supplier and we removed the products from shelves for a full year, helping us save $3 million in spinal implants. Instead of forcing a decision, we empowered surgeons, and they ultimately made the call themselves."

Key Takeaways: What We’ve Learned About Clinical Integration

Clinical integration isn’t about forcing cost-cutting measures onto physicians—it’s about partnership. It takes time, trust, and a willingness to engage in conversations that go beyond price tags. From our experience, the list of key takeaways below are all critical to building and maintaining a clinically integrated supply chain.

- Start by asking the right questions. Too often, supply chain leaders approach physicians with solutions before understanding the problem. Instead of leading with cost, start with curiosity. Physicians are more likely to engage when they see that their expertise is valued.

- Trust is built—or lost—on data. Physicians don’t reject supply chain conversations because they don’t care—they reject them when the data feels disconnected from clinical reality. Make sure the details—outcomes, efficacy, safety, pricing—numbers are right before you present them.

- Lead with clinical outcomes, not cost savings. Doctors don’t wake up thinking about supply chain savings—they wake up thinking about their patients. If they see a product change as a clinical improvement rather than just a financial decision, they’ll engage.

- Find physician champions and let them lead. Physicians trust other physicians more than they trust supply chain administrators. A single engaged physician can influence an entire department, making them one of the most powerful assets in clinical integration. If your organization has a CQVA committee, invite physician champions to ensure their insights are taken into consideration from the onset of an initiative and that they feel heard.

- Be prepared for resistance, but don’t take it personally. Clinical integration doesn’t happen overnight. At first, many physicians will push back simply because they’re used to having no voice in supply decisions. The key is persistence, transparency, and ensuring that when changes happen, they truly benefit both patients and providers.

- Peer-to-peer engagement is a powerful tool. Physicians are more receptive to supply chain discussions when they hear from a trusted colleague rather than an administrator. A respected physician champion can present data in a way that resonates, shifting the conversation from mandates to collaboration.

Final Thoughts

One of the most important lessons we’ve learned is that this work is never truly finished. Supply chain and clinical collaboration isn’t a one-time initiative—it’s an ongoing process that evolves as new data, technologies, and clinical needs emerge. The tools, technologies, and partnerships we build today set the stage for ongoing improvements in cost, efficiency, and patient care.

For hospitals and health systems working toward a clinically integrated supply chain, the most important thing is to stay engaged, adapt, and never lose sight of the shared goal: providing the highest quality care at the best possible value.

For organizations just beginning their clinical integration journey, our best advice is:

- Ask the right questions.

- Build trust with reliable data.

- Give physicians the chance to take the lead.

When supply chain and clinical teams work together, the results speak for themselves.

Patrick Osam, MD, is the Chief Medical Officer of CQVA/Supply Chain at Baptist Health. Guy Love, RN, CNOR, is the Executive Director, Clinical Resource Integration, Providence.